|

|||

|

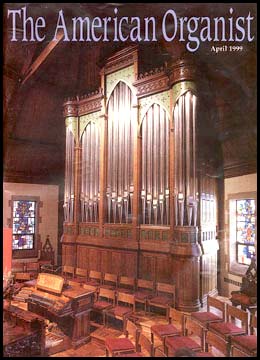

St. Paul's Episcopal Church Opus 70, 1998 Cover feature of the April 1999 From the Organist Very soon after my arrival at St. Paul’s, I was asked by Norman Mitchell, Junior Warden of the Parish, to make an assessment of the existing organ. In the resulting report I focused on the deteriorating condition of the instrument with respect to its action and tonal arrangement. The Organ Committee agreed to study the liturgical, musical and mechanical characters of the pipe organ and to culminate this study with a day tour visiting and recording representative instruments by different builders in the Twin Cities. The committee also reviewed a large archive of reports and documents generated by previous ad hoc organ committees. From this review process was established a theoretical budget for the organ and for renovations of worship space, lighting, sound and acoustics. It was clear that any recommendations should conform to the tradition and aesthetic of Anglicanism, support the mission of St. Paul’s Parish through liturgy, Christian Education and Music Ministries, and be justifiable on moral and economic grounds. With approval of the Parish and the blessing of the Rector, The Rev. Richard L. Matthews, the Organ Committee was authorized to begin serious negotiations for a new organ. St. Paul’s was fortunate to engage the services of David Engen as consultant. He and I reviewed the vision and mission statements crafted by the committee and assembled a packet of data that was sent to organ builders who we felt would best fulfill the vision already established by the Organ Committee. After reviewing proposals from five North American builders and one European builder, the committee settled on two related design concepts presented by Dobson Pipe Organ Builders. Although the original specifications were identical, one design concept placed the instrument in a forward position in the existing organ chamber and featured extraordinary casework. The other concept placed a tall, elegant case in the apse—at the place of the High Altar. This would necessitate the exchange of traditional functions in sanctuary and chancel, the organ case and choir being placed in the existing sanctuary area and a new sanctuary being created in what had been the chancel. This second concept, favored by Dobson, received a less than enthusiastic initial response but, upon reflection, became more appealing when the Organ Committee realized that the new arrangement would project the sound of the organ, singers and instrumentalists directly down the center axis of the nave and bring clergy into more intimate celebration with their worship community. The project received unanimous approval by the Parish at a semi-annual meeting in 1996. During the short two-year period of construction, several visits were made to the Dobson shop—including a busload of enthusiastic parishioners descending on Lake City a few months before the delivery date. The organ was delivered to St. Paul’s in mid-April 1998 and tonal finishing was complete by mid-July of that year. Appropriately, Mr. Engen agreed to present the Demonstration Recital, displaying the vast resources of the new instrument on October 4, 1998. An Inaugural Recital was brilliantly performed by Christopher Herrick on October 20; this recitalist proclaiming the St. Paul’s installation “a world-class instrument”. On the following Sunday, October 25, the Grand Mass in Eb of Mrs. H.H.A. (Amy) Beach was sung by the Parish Choir of St. Paul’s within a context of the Eucharist with Kathrine Handford performing the challenging organ accompaniment. Subsequent festival events included a Dedication Evensong and Hymn Sing presented by the Choirs and Clergy of three Minneapolis Episcopal parishes in the presence of the Diocesan Bishop, and a Concert utilizing organ with a 90-piece Alumnae Concert Band from St. Olaf College. The Twin Cities Chapter of the American Guild of Organists sponsored a Recital and Workshop by Craig Cramer, Organist and Professor of Music at the University of Notre Dame, on February 5. This has been a remarkable experience for me in every respect. It provided the opportunity to work with a group of artisans who advance musical and visual encounter about as far as it can go. It brought energy and a new sense of corporate perception to an established Parish in the city and uncovered a new layer of leadership who now extend this vision to other programs at St. Paul’s. It gave me the opportunity, as Organist and Music Director, to practice a more indirect style of leadership throughout the process and, for this latitude, I am grateful. Incidentally, the Dobson organ at St. Paul’s is also a kick to play!

From the Consultant St. Paul’s organ committee had done a great deal of homework before Greg Larsen asked me to assist them. After surveying many local organists, they had already identified some of the builders they wished to consider. They had an idea of their budget and, in spite of my objections, were firm in their desire to keep the new instrument in the side chamber occupied by the old organ. They had come to a point where the terminology and communication with builders were becoming too confusing. They needed a translator and guide, and that is where I found my role as consultant in this project. I believe that the consultant should act as a resource to answer technical questions and to pose questions the committee has not considered. The consultant should assist the committee in identifying a builder whose style fulfills their needs and whose business practices and reputation are sound. Once the church and the selected builder have established a working relationship, the consultant should withdraw and let the builder do his work, offering opinions only when asked. It is not the consultant’s task to design the instrument. The instrument belongs to the church, not to the consultant. The builder is an artist, and artists do not always do their best work when a third party interferes in the artistic process. Several builders were asked to provide simple preliminary sketches of their thoughts and meet with the committee. (Don’t ask a builder for detailed drawings unless you are willing to pay for his time!) They decided that Lynn Dobson would provide the best instrument for their needs. As the details of the design were fleshed out, I found myself in the middle, asking and answering questions of both parties. There were a couple of miracles along the way. Once the committee saw Lynn’s sketch of how the worship space could be renovated and made more flexible by placing the organ front and center in the chancel, they abandoned the side chamber plan. A more beautiful, functional and less expensive installation was the result. The reduction in engineering costs allowed more resources to go into pipes. Lynn was later contracted to design and build complementary chancel furnishings. The second miracle occurred during a January congregational meeting when the plan was approved. There was no great opposition, but there was concern about financing the project. I was dumbfounded when an elderly woman took the floor and said, “I don’t know about you, but I’ve been living off of the contributions of my predecessors in this church long enough. It’s high time we made a contribution of our own!” In a short time, the entire cost of the project was underwritten. A large two-manual was always the plan. Lynn’s original design was for two manuals, and Greg and I concurred that a large two-manual would be more useful than a skimpy three-manual. An extensive choir program and an unsympathetic acoustic dictated an instrument with quite a bit of sound. With a fairly generous stoplist, there was debate over the peripheral voices. John Panning and I carried on an extensive e-mail correspondence, with Greg’s questions and counsel at all points. What resulted is an instrument that is fun to play, beautiful to look at, and incredibly colorful and versatile. It is easy to service and tune and has been very reliable. When planning the literature for my inaugural program I was flooded with repertoire ideas. It was truly difficult to pare down the choices into a representative program that would demonstrate its many colors. The Dobson crew is to be congratulated on a significant new addition to the already rich organ culture of the Twin Cities.

From the Builder Despite the rise of interest in pipe organs strictly patterned on historic examples, an instrument capable of faithfully rendering the works of many musical traditions remains the holy grail for most organists. Indeed, it is a necessity for most church music programs, which cannot limit themselves to works of a single period or style. It is this situation that has prompted our development of an eclectic approach to organ design, in which the lessons of the last forty years are placed on an equal footing with a desire to play Romantic music and do justice to Sunday morning. Our instrument for St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Minneapolis represents an effort to build such an instrument, one that can render with fidelity the vast majority of church music while giving special emphasis to the solo and choral literature of the Romantic and post-Romantic eras. The design of an instrument worthy of this literature cannot be realized by superficial alteration of neo-Classical principles. The underlying lesson of the great Romantic instruments is the evolutionary advance they represent, building upon the core of their predecessors. Likewise, our thinking must evolve beyond the short-sightedness of the neo-Classical era if we are to produce an instrument that honors Romantic music with sophistication and sensitivity. This is not easy in today’s culture. Evolution implies time—a lot of it—spent in contemplation, trial and error. This century’s advances in transportation and communication have exposed every organ culture to view, and have led to a flavor-of-the-month mentality in which styles are adopted seemingly as readily as one might change a suit of clothes. Unfortunately, it is difficult to understand and impossible to recreate the cultural milieu that produced these historic instruments. On the other hand, by comparison to the protagonists of the American Orgelbewegung, our understanding of Romantic instruments is relatively easier today because our country is filled with splendid examples, from Hook and Johnson in New England to the work of German immigrants such as Pfeffer and Schuelke in our region. Furthermore, despite the fervor of the revivalists, interest in Romantic instruments and composers never really left us. Just as Bach continued to be played from 1880 to 1930, any glance through recital programs from 1930 to 1975 show that Franck, Widor, Reger and Reubke have not been far from our ears. Being surrounded by such a cloud of witnesses from the previous century does not mean that we can easily set aside the Classical understanding we have struggled to acquire over the last half-century. We must put it to use as the Romantic builders did of their heritage, recognizing that there is an underlying continuum of attributes that defines the great organs of every time. Over these universal attributes, such as well-developed principal choruses (the glory of any organ), placement within the same space as the listener (a situation expected for every other musical instrument), an intimate key action (made to be as transparent as possible) and a correlation between the tone of the instrument and the human voice (the first and most elemental instrument)—over these universal attributes we lay the musical and cultural influences of our own time. Although St. Paul’s previous organ, an enchambered and much-rebuilt Austin, was an instrument of three manuals, the physical space in the apse suggested a two-manual organ. We preferred this from a musical standpoint as well, since it would allow us to develop more complete choruses and to include stops that would increase the instrument’s repertoire of color, thereby improving its ability to produce seamless choral accompaniment and a smooth crescendo. The stoplist went through a number of illuminating changes. An independent Pedal Trumpet gave way to a Great Clarion; both of the Great reeds were then made playable in the Pedal. David Engen suggested that the Clarion break to flues sooner than normal out of concern for tuning stability. In response to this concern, we started the flues at e41 and gave them two pipes per note, pitched at 4' & 2', a sort of unison mixture that matches the reeds well and extends their strength and brightness well beyond the functioning range of any reed pipe. The Pedal Mixture departed in favor of a Swell Geigen Principal; to compensate for this reduction of Pedal independence, we pitched the Great Mixture at 2' instead of the more normal 1-1/3' and omitted the break that would normally occur around tenor C, making it more suitable for coupling to the Pedal. Although everyone wanted a Bourdon 32', there simply wasn’t room for such a stop; as a compromise, we provided twelve independent pipes of 10-2/3' pitch for a resultant, and obtained the unison tones from the Subbass 16'. The resulting specification is framed around a 16' chorus on the Great, an 8' chorus on the Swell and a Pedal supported by a Double Open Diapason 16' of wood. Though most principals are made of heavy spotted metal, the mixtures are made of hammered lead and the Great Mixture includes a number of doubled pitches. The combination of lead and high cutups produces a pure tone that is bright without being shrill, something that would be deadly in St. Paul’s acoustic. This tone and the doubled ranks interact to produce resultants that strengthen the fundamental. Most organs from the Classical period have a fairly flat regulation profile. That is, the strength from bass to treble is relatively even within a given stop; further, pipes of a given pitch are the same strength from stop to stop (middle C of 8' and low C of 2', for example). This is especially true for principal pipes. Reed pipes are the exception to this rule: generally, the basses are much stronger than the trebles. In the Romantic era, builders went to great lengths to strengthen the treble of both flues and reeds. This treble ascendancy is a characteristic feature and necessary to properly interpret the melodic nature of the literature from the period. St. Paul’s flutes, especially the three harmonic ones, have obvious treble ascendancy, while the principals and strings have a more moderate increase. The reeds have a generally flat profile. In the case of the Bassoon, Oboe and Great Trumpet, this has been accomplished by providing closed shallots in the bass, where great output would be objectionable in St. Paul’s acoustic. Open shallots have been used in the treble to overcome the natural diminution of strength in reed pipes of higher pitch. The Clarion and Swell Trumpet have open shallots throughout, which gives both the fire and bourdon expected of French reeds. The Trombone is built with resonators of hammered lead and closed, leathered shallots. St. Paul’s acoustic favors lower frequencies, which suits the character of the organ well. Unfortunately, the depth of the chancel, relatively low chancel arch and steeply pitched A-frame roof hinder projection of sound. For this reason, the manual wind pressure was set at 4", with some of the larger Pedal stops playing on 5-3/8" pressure. The manual and pedal reservoirs are large, weighted, parallel-rise bellows; a two horsepower blower and static reservoir reside in the basement under the organ. The design of the white oak casework is inspired by French choir organs. Of course, no choir organ had a façade that began at 16' E, as our example does. However, skillful manipulation of proportions has made the organ’s appearance in St. Paul’s chancel completely natural. The rounded corner towers, a more English characteristic, are perhaps the case’s most remarkable feature, consisting of curved raised panels and framework that turns almost three-quarters of a circle. The Great and most Pedal stops are placed at impost level, the Swell is located in the upper center of the case in a tightly sealed expression box, and the largest Pedal pipes find a home behind the main case. In addition to the organ, our firm constructed the new altar platforms and transformed the old organ grillework into communion railing. The console, detached to permit the placement of two rows of singers in front of the organ case, is elegant not only in appearance but layout as well, the goal being to make an organist immediately comfortable. Oblique drawknobs are set in angled jambs veneered with Carpathian elm burl, piano-scale keys are covered with ebony and bone, and unobtrusive but effective removable lights and mirrors are provided. The key action is carefully engineered and regulated to be sensitive and light, in spite of the relatively high wind pressure and length of certain runs (25' from key to valve, in the case of the Swell). Electric stop action and a multi-level combination action are provided. This instrument represents the latest step in our own evolution. Our first instrument for an Episcopal church with a traditional chancel arrangement was built in 1985 for The Church of the Holy Comforter in Burlington, North Carolina. It was followed by instruments for Ascension Church in Stillwater, Minnesota in 1986, The Church of St. Stephen the Martyr in Edina, Minnesota in 1987 and St. Luke’s Church in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1993. Each instrument gave us the opportunity to learn from talented musicians and to further investigate a musical tradition that is dear to us. We are grateful to St. Paul’s Parish for this most recent opportunity and hope that our work remains for them a source of joy and inspiration for many years to come.

The Dobson Pipe Organ Builders are Lynn Dobson, Ronald Anderson, William Ayers, Lyndon Evans, Randy Hausman, Dean Heim, Scott Hicks, Todd Kauk, Arthur Middleton, Gerrid Otto, John Panning, Kirk Russell, Robert Savage, Meridith Sperling, Robert Sperling, Jon Thieszen, Sally Winter and Dean Zenor. More about this instrument |

||

|

Our Shop • Instruments • Recordings • Testimonials Dobson Pipe Organ Builders, Ltd. Site conception by metaglyph All contents ©1999–2016 Dobson Pipe Organ Builders, Ltd. |

|||

The organ had been built in 1909 for a previous church building and had been relocated in a deep chamber to one side of the chancel in a new sanctuary constructed in 1958. On the basis of this assessment, the formation of an Organ Committee became the first act following Mr. Mitchell’s elevation to the office of Senior Warden in early 1995. The breadth of interests exhibited by the membership of this committee made it the most dynamic group with whom I’ve ever worked in more than a thirty year career in schools and churches.

The organ had been built in 1909 for a previous church building and had been relocated in a deep chamber to one side of the chancel in a new sanctuary constructed in 1958. On the basis of this assessment, the formation of an Organ Committee became the first act following Mr. Mitchell’s elevation to the office of Senior Warden in early 1995. The breadth of interests exhibited by the membership of this committee made it the most dynamic group with whom I’ve ever worked in more than a thirty year career in schools and churches.